Significant ABU Friends

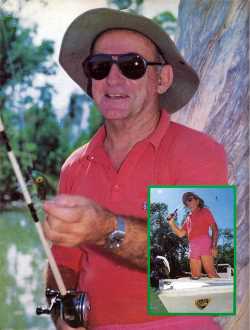

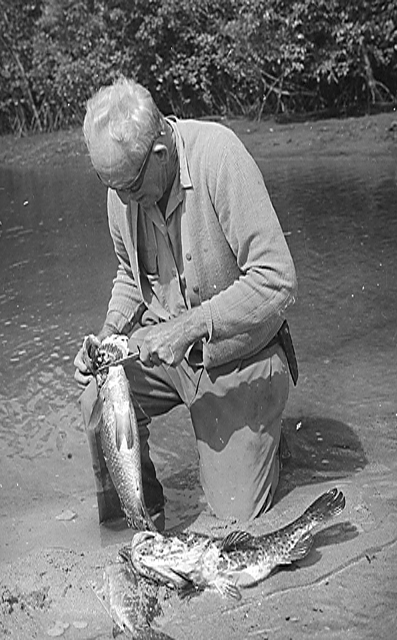

I consider myself fortunate to have actually meet, sit down and chat with Vic McCristal. A very humble man, who attributes my knowledge of him over 40 or more years, to just being in the right place where fish were prolific and his ability to record in pictures and writing his adventures with ABU equipment from the ABU glory days.

A few short years later , I could return the favour and have Vic in my home sharing knowledge of his ABU reels and lure experiences. The first of many more I hope.

Another great man of 90+ years that was also my childhood hero was CO Ericsson 2ic of ABU in Sweden who I am still to meet, but communicate regularly with by e-mail despite his legal blindness and which will take a toll on his flyfishing this year for the first time. Not a bad effort hey! Enjoy reading his story at this link. Incidentally CO and Vic were/are friends, how could they not be, both being held in high esteem in their own countries and visiting each other?

Always an outdoors person as a child, teenager and young man, he eventually settled on Cardwell as home where my mate Gary McCarthy , headmaster at local school in early 70's , had no trouble getting Vic to teach local school kids how to make lures and fish. In his earlier life, before all his books, Vic was much sought after as a magazine article writer for many magazines including my favourite of the time, Outdoors and fishing where he wrote hunting as well as fishing articles.

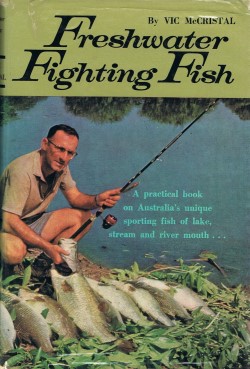

His books included

- Freshwater Fighting Fish

- Top End Safari

- The Family Fisherman

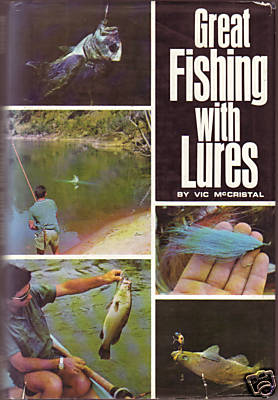

- Great Fishing with Lures (The first I read of Vic's work as a teenager) see below

- The Rivers & the Sea

- Vic McCristal's Fishing Tackle

- The Fisherman's Boat

- Practical Fishing with Lures

Thanks to Tony @ Lure Lovers for permission to use these images.

He is a life member of the National body ANSA since 1980.

The Queensland Chapter of ANSA was formed over 30 years ago in the North (Cardwell) where Vic lives.

Vic recently was noted in The Senior News for his contribution far and wide to helping spread fishing advice to all.

Speaking with President Jeff and life member Vic recently at the ANSA GM saw me receive a typewriter written letter from Vic re his ABU recollections.

This will appear here exactly as proffered (as a scan) shortly, better than my re-word processing! Who uses a typewriter today?

Long may you experience Tight Lines my friend!

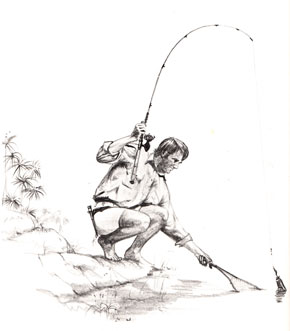

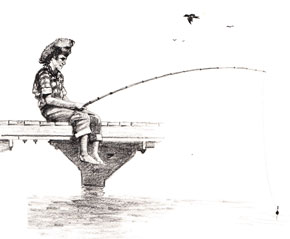

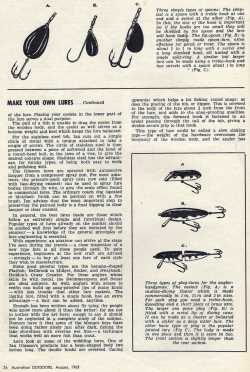

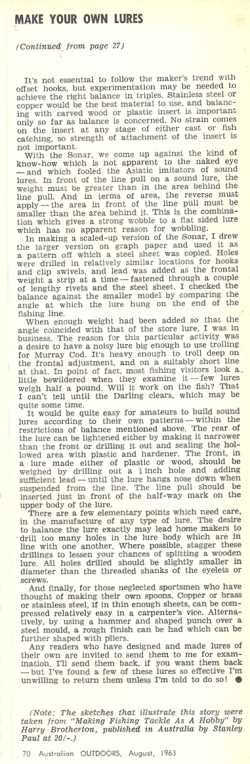

A very obvious addition to Vic's books, eg

"Practical Fishing with Lures", is the inclusion of some beautiful

line drawings which always depict Record/ABU reels, such as the

Record 2100, Ambassadeurs or 444/333 Spinning reels. You can even

discern ABU lures such Hi-Lo, Sonette, Reflex (even bobbing

cork) being used to capture Bream, Flathead, Barramundi and

Yellowtail Kingfish.

|

"A lure is a lie told by a man to a fish!"

Vic McCristal

|

This book has had a profound effect on my fishing life since my teenage years. "Great Fishing with Lures" Murray: Syd/Melb 1970 page7 |

|

PREFACE Since fishermen are human, fish are inundated with forgeries form sublime to incredible. Despite that, or because of it, we know we're no worse than anyone else. Fishermen save their more outrageous perfidy for fish, rather than their bosses or wives. Let's make it clear. Whether it's a worm or a mini-skirt, every bait has a hook in it. You could say civilization is based upon the same principle, maybe known by another name. It might be called an incentive system, health insurance, annual increment or discounts for cash. Yet it's the most effective system, and without it we revert to wars and worse. The development of lure fishing as a major sport is no accident. These last twenty years (ie 50's to 70's Ed.) it has grown from a nappied infant to a muscular adult, with a growth pattern which parallels the motor car in timing, quantity and technology. Fishing today mirrors our technology, and at the same time reflects a basic human need, a need that increases with urban development and population growth. Fishing helps us stay human. Checking back on the long history of lure fishing, the works of Isaac Walton make him the fisherman's Shakespeare. Isaac was revered as the patron saint of fly fishers, and some Australians, therefore look on him with suspicion. They need not. Close reading of his lyrical prose shows that he used bait and setlines cheerfully when he had to. He'd jumped at the chance to use a spinning reel or a sidecast. In so many words, Isaac was actually one of the mob. It's easy to track European and American influence on our fishing. We have trout fishermen who are more English than the English, and plug casters who are faithful worshippers the American cult. Yet the dominant theme of our lure fishing has native roots. It may have been the a cedar-getter who first shaped one of his chips and tied a hook for bass, or a bearded selector who ran out of cicada baits and tried tying a couple of green leaves to his linen line instead. It has grown ever since. Today, fishing is Australia's major participant sport. Of the millions who fish, many use lures - and those who don't usually think about them, wishing they knew enough to have confidence in lures. The mounting pressure for information has resulted in this book. One happy problem attached to this problem, has been the number of interuptions on my doorstep every day of the week. - thousands of people in search of a private odyssey, whether trout, bonefish, bass or barramundi. The reasons for the facination of lure fishing vary from person to person, but they include these: Lures make fishing an active sport. They cover greater areas of water. They catch less small fish. They don't smell or deteriorate. They're cheaper than bait. They're a million different ways. They suit fishermen and and allow room for endless experiment. For reasons of clarity within this book, the word "lure" appies to devices built from material such as wood, plastic, rubber, various metals, usually in imitation of natural food. The word "bait" implies natural flesh of some kind which is more or less a fish's natural food. ........................................ |

|

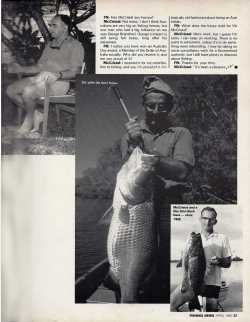

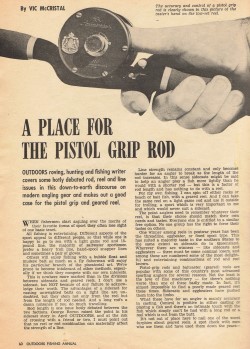

Interview with Vic McCristal: Father of Sportsfishing

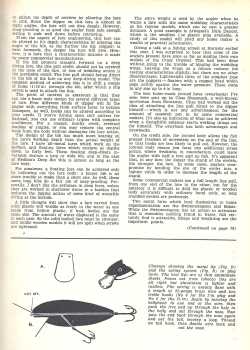

Vic McCristal makes his own Lures

A look at one of his tackle boxes before plastic was commonplace.

Vic was welcomed in the Tight Lines Catalogues by the then ABU company of Sweden, to offer his experience with their product in the wilds of downunder Australia.

Its tough tropical freshwater and saltwater species, like barramundi, Javlinfish (grunter) threadfin salmon, tarpon, and the tackle busting fingermark not to forget the adrenalin rush pelagics like the many species of mackeral, queenfish, trevally, turrum, snub-nosed dart (permit) and the occasional spool-emptying bonefish, would test the BEST of tackle. ABU survived and Vic's 40+ year old Ambassadeurs still catch fish today!

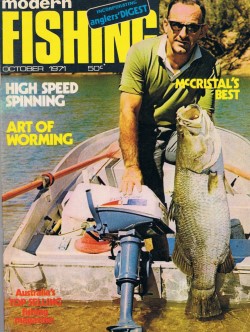

Vic was and is still a very respected Australian fisherman featured in many Australian Fishing magazines.

Here we see 4 different types of ABU reel; Ambasadeur, Spinning, 500 series and fly reels being used! |

|

|

|

|

The story of this barramundi capture is

here. Page 1 Page 2 |

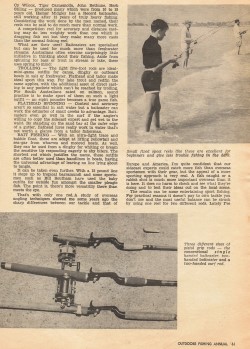

He was responsible for so much wonderful fishing writing in the 50/60/70 that I feasted on it as a young fella! Much was featuring the fabled ABU brand, then relatively new to Australia, and such a quantum leap ahead of other available fishing equipment.

Not only was he interested in ABU's fine reels, but all the product line available. I saw my first ABU Speedlock pistol grip rod, the wonderful 662 ABU Diplomat double handed baitcaster here in this article. I was not until 5 years later I bought one in London. I still have it!

Vic was a prolific fishing writer and photographer and will be a hero to me for as long as I am still able to realize that ABU was the best available. He took me on the path of righteousness in my selection of rods, reels and lures! ..and no doubt his influence fell upon many .

More of Vic's articles/books will be linked elsewhere as time permits.

Co-Published with agreement from Anthony Gomes of CCC and Vic McCristal

The Case for Clear - by Vic McCristal.

The Shadrac with modified hooks. This used to be one of my secret weapons in clear plastic. Most lure manufacturers lack the confidence to build many clear plastic lures, possibly because most fishermen fail to recognise/buy them.

Most fishermen develop personal theories about colour. As time passes, we adapt to changes that we see and results that show up. If we travel, we discover the regional variation in taste which is often led by a locally successful leader. I saw many different tastes evident when I travelled interstate, and being born a lateral thinker, I often used something different to the local favourites.

The thinking was that if you already know that Brand X works well, an experiment will often add to the picture. There are times it pays off, and other when it just takes you nowhere. For example, after a number of trips to the coast around Albany, WA, I tried to discover a lure that worked as well as the local choice for a herring lure. North or south, the WA crew used a tiny home-made or improvised piece of plastic, originally used as a nail or screw plug for concrete walls. Each time I visited, I used other types of lure. Nothing ever worked so well as those little wall plugs. I’ll bet they are still using those wall plugs.

Fishermen often favour a particular colour in lures. Some of us change according to conditions. Study any lure and it uses assets like colour, shape, depth, action – but it will always need to be cast and worked in the right place at the right time. I’ve used a number of types of clear plastic lures, and all worked well. But that doesn’t mean much when you can also use totally black lures with equal success. I still pride myself on a black Heddon Deep 6 which caught various species of fish in deep water on moonless nights. Modern fishermen have much better technology – I took a fair while to get around to the echo-sounders which we now use as standard gear.

We learn much about colour from the bait we use. One problem is that some of these change colours, mostly when under stress. Think about squid, or octopus, or even predatory species. We don’t need to see many barramundi before we discover an occasional head stripe. What we do know is that fish use a lot of bosy language and we exploit that with our lures. So there’s nothing radical about a clear plastic lure. They still carry hooks, and can be built as strongly as their siblings. It’s possible they make it harder for fish to discover their real identity. One of my favourite lures ended up somewhere among the corals of South Brook Island.

It was a fitting end for what had been a long and successful career. Where it originated, in the United States, it was known as a Shadrac. The first thing I noticed was the clear plastic. I added some hooks to fit my own ideas, but left the modest little frontal propellor alone. Mostly it was employed as a casting lure around the local mangroves, but it also did sterling duty over shallow coral.

In the mackerel season, I used it for trolling when nobody could see what I was using. That was how it was lost, and I can only hope that a fellow fisherman later found it washed up some place.

Clear plastic has the same weakness as most other colours. Long exposure to sunlight will weaken the plastic. We all benefit when we protect out plastics from long periods of sunlight. This applies to all our gear – rods, lines, lures. Heat usually goes with sunlight, and I’ve seen hollow plastic lures swell to distorted and useless shapes after being left in the sun for too long. I have no evidence that clear plastic is more durable, or less durable, than any coloured plastic. It makes sense simply to use your tackle and then to keep it under cover.

Most of us have had minor disasters when lines suddenly snapped for no apparent reason. A few weeks of sunlight and heat is most likely the cause, but it goes unrecognised. About the worst way to weaken plastic of any kind is to leave it in your boat or car between fishing trips. Although I used braid lines (still do) for both trolling and deep water, I don’t yet know how it stands long periods of sunlight. The obvious experiment would be to leave a short length of good quality braid out for a few weeks of sunlight, then test it for breaking strain.

Braid line is not a “clear” plastic, as some types of nylon are, but to exploit colours we need to consider more than making it hard to see. I often used a bright red or bright yellow nylon line to fish rainforest creeks or mangroves. It helps to see your line in flight when you’re casting.

Any doubt about fish “seeing” the bright nylon disappears once you’ve caught a few. In my case, I could never notice any difference in results, and results are what count.

I’ve been asked more than once about how to go about writing. My advice has always been – “Do your fishing first.” After that, of course, comes the need to observe accurately and write honestly about what you see. A thinking fisherman always has plenty to write about.

Saratoga by Vic McCristal.

I don’t know anyone who knows for sure how the saratoga was named, but it is generally accepted to be a handy corruption of “Ceratodus.”

If you need to be fussy, other versions of the same species are known as Scleropages jardini and Scleropages leichardti.

A portable glass-fronted box allowed this photograph of a saratoga under aquarium conditions – it also allowed return.

The first I caught were from the upper Dawson River. I added what might be other varieties of the same species further north, varying between the Jardine River (tip of Cape York) and rivers and lagoons in the Gulf country and then into the Northern Territory, including Arnhem Land and the area now known as Kakadu. I’m pretty sure you’ll never find them further west than Darwin – I know some potent fishermen who’ve tried.

The saratoga is popular for several reasons. When I first saw them cruising the surface of river backwaters, I recognised a surface feeder. True, they’ll also take a lump of meat beneath a cork float, or a freshwater shrimp or any kind of fish bait, but nothing beats casting to a fish you can see. They make a classic target for a surface fly, or again for a surface popper of almost any kind. The growth of fly fishing owes one of its many debts to saratoga.

Although they’ve existed for millions of years, they grow only slowly. I suspect they are an easy victim for sea eagles, or any of the fish-hawks, and this might account for them being a buccal (mouth-breeding) species. The almost marble-sized eggs are first held in the mouth. Juveniles from these eggs also shelter inside the mouth, and despite relatively low numbers of eggs (30 to 50) they make wonderful survivors. Fossils indicate that they have been around for many millions of years, and various species are found in other parts of the world, such as the Amazon delta, Indonesia, and in Africa.

Despite their low breeding numbers, they’ve been welcomed by sporting anglers who recognised their value. Since Australian anglers have travelled overseas in pursuit of other species, we can expect a few specialists to go looking for such as the giant arapaima, of the Amazon.

Where they have been stocked successfully in Australian dams, saratoga are a serious status symbol. Fishermen are happy to take a picture and release saratoga. They aren’t a good table fish, comparing poorly with others available, including bass, yellowbelly, Murray cod, eastern cod and others.

The biggest I’ve seen was about 80cm long, but the textbooks say they grow longer and to weights up to 10kgs. Much depends on the location – for example, those from the Jardine River are mostly taken from small patches of lily pads adjacent to flowing water. The Jardine runs fresh almost to the mouth, but for much of its short length is adjacent to swamp country on the western side. I’ve always suspected that these swamps hold saratoga but it is ideal crocodile country. If you like that kind of adventure…..

East of the Jardine are smaller streams where I’ve caught such as banded grunter, the aptly named “Mouth Almighty” and archer fish. Saltwater fishing is often spectacular, and you’re dealing with the troubled tides of Torres Strait, so exploration would take time.

I’ve been told of professional guidance now available and I hope my friend Gary Wright is still among them. Those who explore for saratoga in this country will discover something totally new to them, but they won’t be the first to do so.

About 30 years back, I met one such explorer in the person of an American lady, Kay Brodney. She had retired after a working life as librarian to the United States Congress, and was seeking Australian saratoga in Borumba Dam. Borumba was first stocked by Hamar Midgley. Kay Brodney had developed an ambition to catch each of the widespread Scleropages family in each of its’ homes around the world – on fly.

It was a sturdy ambition, and I hope she succeeded. These personal fishing targets are often more difficult than we expect. At one time, I had hopes of catching all of the species native to this country. I ended up in the 30’s before growing too old to worry about it, but at that time I knew there were at least 50 freshwater species able to be caught by our usual angling methods.

Progressive biologists have since divided species more accurately, so anyone taking that personal path might be chasing more than 50 species. Fish identity is often made by counting fin-rays or patterns of scales. As a born cynic, I suspect our biologists will still have projects and problems with fish identity long into the future.

Saratoga will never be a commercial species. If we treat them as they deserve, they will benefit generations of fishermen yet to be born.

One Teacher – By Vic McCristal

By Vic McCristal

Meunga Creek enters the sea a couple of miles north of Cardwell. It must have been about 1965, and I had walked up the creek on a low tide. Eric Moller had walked downstream to check a crab-pot.

I still recall that day, and the way we clicked without much being said. I was using a baitcaster and lures. Eric must have been impressed with my results, but typically said nothing. He simply arrived on my doorstep a few days later with similar tackle, and rapidly showed natural casting skill.

That part of it came from being a top rifle shot, and the best part of a lifetime spent on boats and in the bush.

He taught me about the creeks and rainforest around Cardwell and Hinchinbrook.

He had one problem. Maybe two. First, at the age of 50 he had been carried out of the bush with severe angina, and he would not stop fishing. Second, he started to lose good lures and occasional good fish, to a point where his invalid pension couldn’t support the cost of commercial lures. I steered him towards making his own.

While my own patterns were less than wonderful, Eric quickly started improvements. He had access to white beech and red cedar, both of which he knew from his time on fishing boats. This gave him all that was necessary for entry into lure-making. His workshop was an old corrugated iron shed in his back-yard, where he converted slats of beech and cedar (and sometimes other timbers) into lures.

Most of the Moller lures were made in those years between 1966 and 1975. I was in my writing prime around then, and so was able to fish with Eric pretty often. We were both early risers, fishing the best tides and weather that Hinchinbrook and the creeks around Cardwell had to offer. When weather or tides were bad, Eric would spend more time in his shed and I would turn to the typewriter.

When I was absent on one of my trips interstate, Eric fished with other friends – who were plentiful. The ever-present risk of a fatal angina attack encouraged him to fish in company, though he seldom talked about it.

He mentioned it to me once when we were out in Missionary Bay. I had offered to go home when he seemed to have gone quiet, plainly off colour.

“No” he said. “I know I might drop, any time. If it should happen, just go on fishing. I’ll be the friendliest ghost anyone meets around the mangroves”.

He was generous with his lures, and probably gave away most of those he made. Like many grandparents, he was easy with young fishermen. Teenagers are often a bit awkward in adult company, but that was never the case with Eric. His shed was also home for a flock of homing pigeons, and those times are easy to recall….the pigeons cooing from the hardwood rafters, and Eric guiding a couple of his many visitors towards making their own lures and giving them a couple of his own to use for patterns.

I was able to arrange the supply of quality Eagle-Claw trebles and strong split rings, and it was inevitable that others supported him with timber for bodies, wire for eyelets and sometimes sheet metal for bibs. If I remember correctly, one friend even supplied him with a cutting press for Zincanneal.

His main tools were an old-style hand drill and a well-worn Schrade pocket knife. What helped him most was a keen eye and a close study of the fish he caught. Basic carpentry tools including a metal square and a plane were topped off with a few different grades of emery paper.

He always stayed with some ways of his own. Although the lures were widely accepted, his paintwork was nothing to skite about. He always pointed out that fish were fish, “not bloody art critics,” which is true. My response could have been that fish don’t buy lures – which didn’t really matter to Eric. Most of his lures were simply given away, anyway.

To-day’s generation of lure collectors are well aware that Eric’s lures might turn up anywhere, even interstate, even in distant garage sales. Moller lures has plenty of copies, and I’m never surprised to be asked to identify an original Moller lure. There are many collectors, of course, and finding an original Moller – well, they now run to a startling price, and I doubt if their maker would approve.

I doubt if he ever built a lure that was meant only to catch anything but fish. Eric was certain that his lures worked, and he usually insisted that visitors use his lures in good country. Apart from his fishing skill, he was an astute judge of people, and seldom lost an argument.

On one trip I set out to prove a point. At the time, I had been getting results with surface poppers. I knew that individual skill counted as much as lure style. Eric accepted my challenge, but didn’t seem happy about doing so.

On our return home, I pointed out that our results were about equal.

Eric frowned, and flattened me with his reply. “It proves nothing,” he said. “You can catch fish on just about anything.”

He was right, but so could he – and thousands of other fishermen. His faith in his own lures was more than justified, and I still have one of his specials. These were usually crafted from red cedar, beech or Huon Pine. My own weakness was for lures from the old red cedar stumps, the buttresses of which often carried a fiddleback grain. Mine were varnished with clear epoxy. The agreement was always that his lures were to be fished with. I never told Eric, but I only caught one barra with that special lure before setting it aside.

Some of my collector mates have dozens or even hundreds of Moller lures. I have only one, and I’m keeping it.

End Note:

Early Sportfishers included quite a few who are still alive. In the early 1960’s, we were influenced by US magazines, such as Field and Stream, but line sizes were less important to the Americans – and their fishing was different.

The Australians view favoured treating our own species, and we had hundreds of varieties of fish unknown overseas. ANSA has always been democratic and inclusive. We had no real choice but to set up an independent association. Other organisations covered only limited fishing, we saw wide open fields such as fly fishing and even sidecasts, and empty dams waiting to be stocked with native freshwater species. We’ve changed all that, and it did not take long.

And Queensland may have been at the forefront, but we weren’t alone. One of my early pictures at a meeting of fellow spirits in Manly, Sydney, shows younger versions of Jack Erskine, Clyde Kelton, John Bethune, Vic McCristal, Rod Harrison and Don Brooks and somebody whose name escapes me, and none of us had the remotest idea that our efforts would lead into the kind of future we see here to-night……

This entry was posted on Wednesday, September 29th, 2010 at 9:25 am and is filed under Articles, FNQ, Fishing, Vic McCristal. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

If you are a person that has significantly had an effect on design/development/testing of ABU equipment over the years please contact me wayne@realsreels.com if you wish your contribution documented for posterity and the immediate interest of the ABU fans worldwide!